Background

The America Invents Act shifts the United States from a first-to-invent to a first-to-file patent system. This eliminates the need the determine the first inventor, and thus the AIA eliminates patent interferences, and instead provides a new procedure – a Derivation Proceeding – for determining whether an earlier filed application was derived from the inventor of a later filed application.

New 35 U.S.C. §135(a) entitled “Derivation proceedings” provides:

An applicant for patent may file a petition to institute a derivation proceeding in the Office. The petition shall set forth with particularity the basis for finding that an inventor named in an earlier application derived the claimed invention from an inventor named in the petitioner’s application and, without authorization, the earlier application claiming such invention was filed. Any such petition may be filed only within the 1–year period beginning on the date of the first publication of a claim to an invention that is the same or substantially the same as the earlier application’s claim to the invention, shall be made under oath, and shall be supported by substantial evidence. Whenever the Director determines that a petition filed under this subsection demonstrates that the standards for instituting a derivation proceeding are met, the Director may institute a derivation proceeding. The determination by the Director whether to institute a derivation proceeding shall be final and nonappealable.

The USPTO estimates that there will only be about fifty Derivation Proceedings a year.

Timing

New §135(a) requires that the Derivation Proceeding be initiated within one year “of the first publication of a claim to an invention that is the same or substantially the same as the earlier application’s claim to the invention.” This is echoed in proposed 37 CFR §42.403, and is similar to the language in old §135(b)(2) pertaining to interferences, but it leaves some inexplicable gaps. For example what happens if the one year from publication passes before offending claims are presented in the earlier application?

Initiating

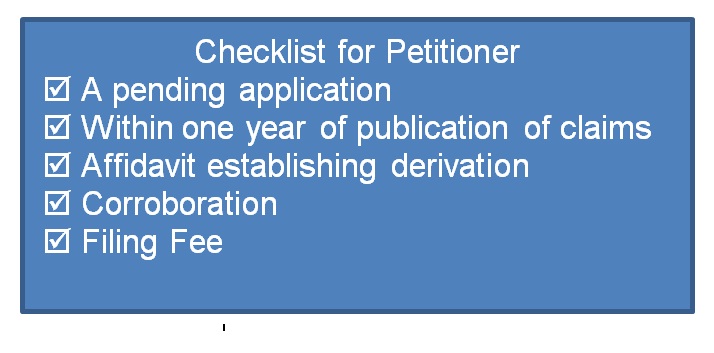

A Derivation Proceeding can only be initiated by a patent applicant (proposed 37 CFR §42.402) which includes a reissue applicant (proposed 37 CFR §42.401). The petition must:

- Show that the petitioner has a pending application, and the petition is being timely filed. Proposed 37 CFR §42.405(a)(1).

- Show that the petition’s application contains at least one claim that is substantially the same as the respondent’s claimed invention (proposed 37 CFR §42.405(a)(2)(i)) that is not patentably distinct from the invention disclosed to the respondent (proposed 37 CFR §42.405(a)(2)(ii).

- Provide sufficient information to identify the application or patent for which the petitioner seeks a derivation proceeding. Proposed 37 CFR §42.405(b)(1).

- Demonstrate that an invention was derived from an inventor named in the petitioner’s application and that the earlier application was filed without authorization. Proposed 37 CFR §42.405(b)(2).

- Show why the respondent’s claimed invention is not patentably distinct from the invention disclosed to the respondent. Proposed 37 CFR §42.405(b)(3)(i).

- Identify how the claim is to be construed. Proposed 37 CFR §42.405(b)(3)(ii).

Overall, the petition must be supported by substantial evidence, which at a minimum would include an Affidavit addressing communication of the derived invention to the respondent, and respondent’s lack of authorization to file. Proposed 37 CFR §42.405(c). The showing must be corroborated. Proposed 37 CFR §42.405(c).

The petition must be accompanied by the derivation fee, currently expected to be $400 (proposed 37 CFR §42.404) and must be served upon the respondent (proposed 37 CFR §42.406). Proposed 37 CFR §42.407(a).

If the petition is defective, the petitioner must correct the defects by the earlier of one month from notice of the incomplete request, or the expiration of the statutory deadline in which to file a petition for derivation. Proposed 37 CFR §42.407(b).

The determination by the Director whether to institute a derivation proceeding is final and nonappealable. New 35 U.S.C. §135(a).

Determination

The Derivation Proceeding is decided by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) (new 35 U.S.C. §135(a); proposed 37 CFR §42.408), unless the parties opt for arbitration (new 35 U.S.C. §135(f); 37 CFR §42.410), which is dispositive as to the parties. The proceeding is a trial governed by the Subpart A regulations. 37 CFR §42.400(a). The final decision of the PTAB, if adverse to claims in a pending application constitutes a final refusal of those claims, and if adverse to claims in an issued patent, constitutes cancellation of those claims (unless appealed). New 35 U.S.C. §135(d). The PTAB also as the authority to correct the naming of the inventor in any application or patent at issue. New 35 U.S.C. §135(d). The PTAB decisions are generally public record. 37 CFR §42.412.

The PTAB can defer action on a derivation proceeding until three months after a patent issues on the earlier application, or stay the derivation proceeding until the termination of a Reexamination, Inter Partes Review, or Post Grant Review. New 35 U.S.C. §135(d). The PTAB can also decline to institute a Derivation Proceeding if where the patents/applications involved are commonly owned. 37 CFR §42.411.

Settlement

The parties to a Derivation Proceeding can terminate it by filing a written statement reflecting the agreement of the parties as to the correct inventors of the claimed invention in dispute, and the PTAB will act accordingly unless the agreement is inconsistent with the evidence of record. New 35 U.S.C. §135(e); proposed 37 CFR §42.409. The settlement agreement must be filed with the Director, but upon request will be treated as business confidential information, and only made available only to Government agencies on written request, or to any person on a showing of good cause. New 35 U.S.C. §135(e).

Recommendations

Inventors who thought that the AIA would dispense with the need for inventor notebooks are disappointed. The date of invention, and in particular whether it is prior to or subsequent to a third party disclosure, is the central issue in a Derivation proceeding, and the inventor will want proof of these events. Moreover, it is more important than ever to document what disclosures are made and to whom, in order to prove derivation. Not surprisingly under a first-to-file regime, getting the earliest filing date possible is the best plan, and getting a filing date before any outside disclosures eliminates the possibility of derivation.

Derivation proceedings are more likely to result from attempted collaboration, than outright theft. After the inventor of A and the inventor of B have some preliminary talks, and the inventor of A begins to think about A + B, while the inventor of B begins to think about B + A, the difference between building on the prior art and derivation begins to blur. An agreement prior to the discussions could avoid at least some these difficulties.

To avoid derivation proceedings, then, one should try to limit third party disclosures until after at least a provisional application has been filed, and address the ownership issues in the confidentiality agreement covering the disclosure.